You have probably experienced a situation where someone asked you something, and you totally couldn’t remember what it was about. Or you wanted to say something in English, and the word was on the tip of your tongue, but yet you couldn’t remember how to say it.

Why did this happen?

Our brains are designed to forget most information. In the evolutionary pathway, the most important thing was to assimilate those pieces of information that led to survival, such as finding food or reproduction.

Moreover, forgetting is a necessary process for optimizing the performance of our memory. There is a very rare disorder called Hyperthymesia. People affected by this disorder are able, without effort, to recall in great detail most of the events of their lives. It turns out that these people are unable to function normally. From their descriptions, it appears that they are overwhelmed and tired by the never-ending influx of memories, which are without any relevance to their current functioning.

This means that remembering information that the brain may judge as less important (English vocabulary, for example) involves effort. Your learning of a foreign language is, de facto, a battle against the process of forgetting.

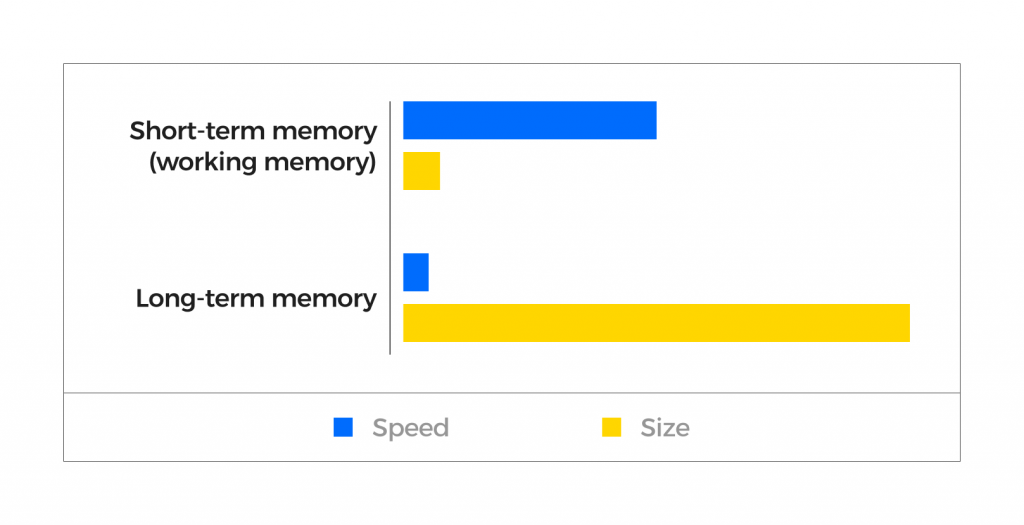

There are many types of memory, which have different modes of operation and different purposes. Depending on the situation and type, information is stored in the right place and in different ways. In this article, we will focus primarily on short-term and long-term memory (including declarative and procedural memory).

But what distinguishes each of them and how does it relate to language learning? Let’s take a look.

Short-term memory

Memorization begins precisely by using short-term memory, also known as working memory. This is the area that the brain engages, for example, for the task of repeating a just-heard sequence of numbers in reverse order. Try to remember this sequence “8-2-4-9-1-3.” Now close your eyes and replay it from the last to the first. Whether you succeed depends on how good your short-term memory is just now. Regardless of the result, however, you won’t remember anything in two hours. And that’s because this memory stores information for a few seconds to a few minutes.

Any knowledge we acquire must first pass through the short-term memory phase. Then the brain decides whether the newly acquired information will be stored in the long-term memory or discarded. In other words, what we remember is filtered by the brain, which decides what is relevant to it. Therefore, it is important to learn a new language in a way that our brain will interpret as relevant. In this way, you will “send” the information further and thus be able to use it later, for example, during a conversation.

Short-term memory can be compared to a funnel through which water is poured. Water in this context symbolizes the stream of words and sentences we are trying to learn. It is advisable to pour them in slowly and systematically so that all the contents can flow freely. Pouring too much, too fast, can cause the funnel to clog and lose the contents. When you are learning languages, you may overdo the amount of material. During a session, you may think you are doing a lot in a short period of time, but in reality you will remember very little. That’s why it’s important to optimize our learning patterns. Only then will the data go further, that is, into the long-term memory.

Long-term memory

So what is the difference between long-term memory and short-term memory? This is indicated by the name itself. Long-term memory is a type of memory that allows you to store information for a longer period of time. Data remains in the long-term memory from a few minutes to the end of your life. It is through this memory that you can remember facts, events, skills, and experiences.

In the case of learning a language, it is necessary for information such as vocabulary words, grammatical rules, sentence constructions, etc. to go into your long-term memory. At the right moment, for example, during a conversation, the data stored in the long-term memory will be read out.

How do you transfer words and sentences from the short-term memory to the long-term memory? By appropriate repetition. Studies show that the memorization process is spread out over time. Even repeating the same information multiple times in the short term has virtually no effect on our ability to reproduce that information in the long term. A good example is the number of a hotel room on vacation (or the access code to that room). After the first few repetitions, we use it without error. Unfortunately (or fortunately), you are unlikely to recall it a month after returning from vacation.

The mechanism of the Spaced Repetition algorithm was described more than 100 years ago, and it is one of psychology’s most spectacular discoveries when it comes to a method of effectively repeating and remembering information.

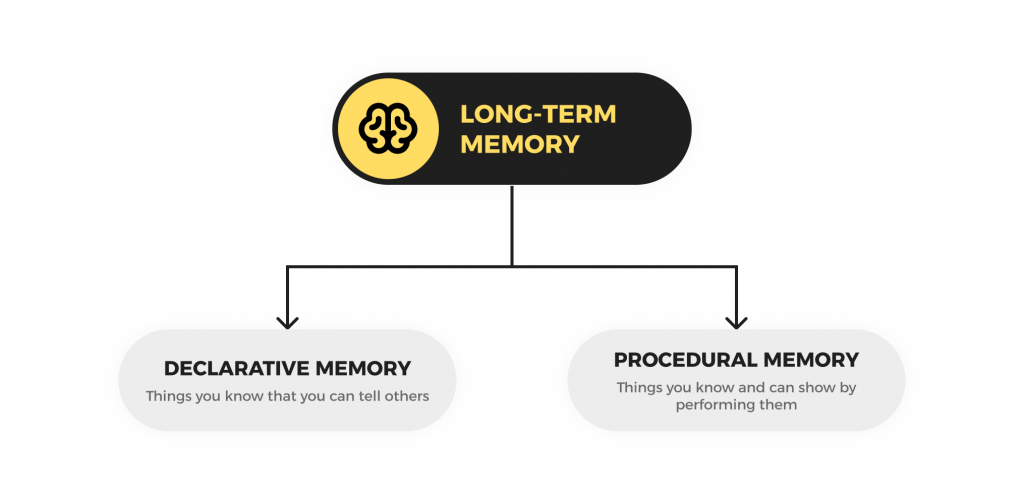

However, is it enough to commit data such as words and grammar rules to the long-term memory? Will we then be able to communicate fluently in a foreign language? Unfortunately, not necessarily. This is because there are two types of long-term memory involved: the conscious (so-called declarative) and the unconscious (the procedural)

Two types of processes

What is crucial to understanding how to learn language effectively as an adult, is the specialization of long-term memory into a conscious (i.e., declarative) and subconscious (i.e., procedural) part. This division was proposed by Scoville and Milner in 1957, who studied a patient named Henry Molaison.

- We use the conscious part to “declare” facts, such as dates, tasks or methods. These are things you know and can tell others. If I ask you what year you were born, you just tell me.

- On the other hand, there is subconscious memory and you use it when you act instinctively, such as riding a bike, being afraid of a spider, etc. These are things that you know, but which you can show through action – if I ask you if you can play the piano, you have to play to prove it.

A growing body of evidence suggests that language depends largely, if not entirely, on unconscious memory. Exactly as with other complex sensorimotor skills, such as playing soccer or the piano.

Declarative memory (the conscious thinking)

Declarative memory (also called descriptive memory or factual memory) is a type of memory that is responsible for storing information and knowledge about facts, events, data, places, people, etc. Such conscious memory allows us to store knowledge of individual words and grammatical rules. Unfortunately, it is not enough to let us speak the language fluently.

Although in theory you may know a lot of vocabulary and rules (because you have them stored in your conscious, declarative memory), you may still not be able to communicate fluently – the process of speaking in a foreign language, as in the native one, must be “automated” as much as possible. If the information is stored only in the declarative memory, you will get tired trying to “consciously” find it. This is what happens at the beginning of learning a foreign language. You stutter and get confused and have great difficulty in piecing together meaningful speech. And yet speaking in English is completely effortless for you.

So what else needs to happen in order to use a foreign language fluently? The information must be automated, and therefore transferred to procedural memory.

Procedural memory (the unconscious thinking)

In contrast to declarative memory is procedural memory. This is a specific type of memory characterized by the ability to perform certain types of tasks without awareness, in an automated manner.

The processes directed by procedural memory usually take place below the level of conscious attention. These tasks range from tying shoes to reading or riding a bicycle. Think of it this way: you never consciously think about balance and frictional force while riding a bicycle. And yet you ride.

In order for you to be able to use language fluently and with confidence, you need to transfer your knowledge from the conscious level – declarative memory – to the unconscious level – procedural memory. In this way, you will automatically know how to use language structures, including grammar and sentence construction, and combine words with each other to form sentences. Speaking will then become effortless, and words and sentences will come to your tongue on their own. Put another way, you will begin to “feel the language” and use it intuitively, knowing what is correct and what is not, without consciously thinking about language rules or principles. When the process of using the language is automated, you will gain fluency.

So how do we transfer our knowledge of language from the declarative to the procedural memory? By repeating whole sequences of words – sentences, phrases, collocations. In this way, a grammatical rule stored in the declarative memory will have its representation in procedural memory. Speech is a sequence of words. Note that even in your native language you are not able to repeat the words of a song beyond a few lines the first time, even though you know the language perfectly.

As you learn the language, you will have to practice the shorter and longer elements of your “song” until linking them together becomes subconscious. Learning the elements is a staggered process. However, time is not the only factor that affects the effectiveness of the whole process. It is useful to know what other factors affect the success of our efforts.

Why is this important for language learning

Why am I even bringing this up? Because of two super interesting facts.

- Research indicates that activation of the conscious memory system can suppress activation of the unconscious memory system. This means that deliberate attempts to learn specific information can interfere with subconscious learning of patterns and intuition. That is, in other words: the more we try, the worse we do. This explains why adults have such problems learning languages.

- On the other hand, conscious thinking in children is not well developed, so their language skills immediately go to the subconscious part. This explains why children learn language with such ease.

This suggests that for effective language learning, we should look for ways to “turn off” (or at least “mute”) our conscious thinking.

It has been confirmed in numerous studies that such things as sleep deprivation, physical activity, or most interestingly, “alcohol consumption” just mutes conscious memory (i.e., turns off our logical thinking), which may explain why it is easier to speak a foreign language when drunk.

The problem with these techniques is that they are not permanent and practical. We can’t be sleep-deprived or drunk all the time.

Conclusion

So how do we transfer our knowledge of language from declarative to procedural memory? By repeating whole sequences of words – sentences, phrases, collocations. In this way, a grammatical rule stored in declarative memory will have its representation in procedural memory, and the usage will become automatic and autonomous. Speech is sequences of words. But you’ll read about it in our article on learning language with complete sentences.