I started my adventure with foreign languages back in elementary school, when I was 13 years old. I grew up in post-communist Poland, so learning languages was not the norm. Few people went to language courses, mainly because they were expensive. I was lucky – my aunt Małgosia from Austria visited me and decided to enroll me in a German course. At the time I did not realize the significance of this event. This was the beginning of not only my fascination with foreign languages, but also the story of the creation of a particular version of the spaced repetition algorithm, and with it a language learning tool that actually works – Taalhammer.

In this article, I’ll tell you that story and describe the details of the spaced repetition algorithm, arguably the most powerful technique that exists to improve the brain’s ability to absorb information.

Read on!

- My adventure with spaced repetition – part one

- Learning in intervals

- Hermann Ebbinghaus and the forgetting curve hypothesis

- Spaced Repetition

- SuperMemo – using repetition of material at set intervals for language learning

- Time for repetition – how does it work?

- My adventure with spaced repetition – part two

- My adventure with spaced repetition – part three

- My adventure with spaced repetition – part four

- Can you learn even more efficiently?

- Atom – new algorithm, even better language learning

My adventure with spaced repetition – part one

In the introduction I mentioned my aunt from Austria. In 1992, the same aunt presented me with my first computer, with the Windows 3.11 operating system, for my sixteenth birthday. If you are one of the younger readers, I just want to remind you that in those days, mere mortals couldn’t even dream of the Internet – they probably hadn’t even heard of it.

It was the beginning of high school for me. There I met Michał (I called him Wiórek, which translates to Chip), who showed me the SuperMemo 6 program for the DOS operating system. It was the first computer program for learning foreign languages. It was then that I first encountered the Spaced Repetition System (SRS) method of interval repetition.

But don’t be fooled – the program resembled nothing you might now associate with language learning applications. Take a look at the screenshot!

The program also did not have any ready-made courses or materials. Michał and I used it to learn German, so we had to input materials from textbooks or other books ourselves. Then we used it for years until high school graduation, and the results surprised us incredibly. Even at school events for fun we quizzed each other on vocabulary, to the surprise of others. We were not able to forget what we had been learning, and these were thousands of words and sentences!

Why was this happening? What was so special about the SuperMemo program?

Let’s start from the beginning.

Learning in intervals

Our brains are wonderful tools that can remember as well as forget information. The human brain was primarily focused on remembering facts that helped us survive, such as reproducing or finding food. In turn, the information that was not relevant at the time was forgotten.

So in order to remember a lot of material – and this is the case with language – we need to counteract our tendency to forget.

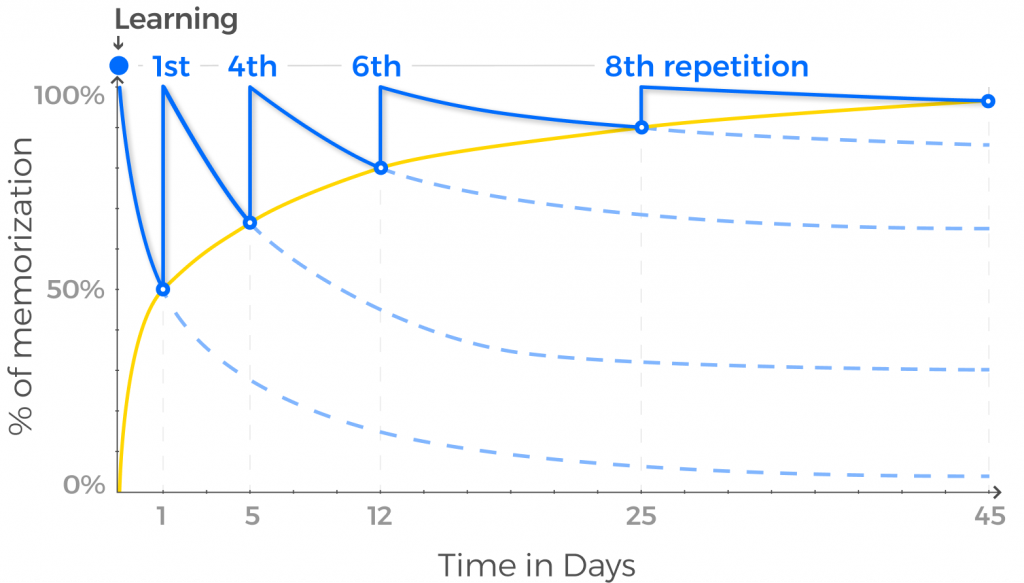

The spaced repetition method involves asking a person to memorize a fact – in the context of languages these may be words, sentences or rules. The given material is repeated several times, but the intervals between repetitions increase each time. If a person can recall a given piece of information, the time interval is lengthened, and if not, it is shortened. So after a while, you repeat more often the things that are difficult, and less and less often the things that are easy. In this way, the information stays in your memory for longer, and you can remember about 95% of the material, or even more.

Hermann Ebbinghaus and the forgetting curve hypothesis

Research on spaced repetition has been conducted for over 150 years. The basis for research on this method was the work of Hermann Ebbinghaus, who suggested that the loss of information over time is subject to what is known as the forgetting curve, but that forgetting can be reset through repeated exercises based on active recall of information. Perhaps you’ve heard the expression that repetition is the mother of learning (from Latin, repetitio est mater studiorum)? This is certainly true.

Between 1880 and 1885, Hermann Ebbinghaus conducted a limited and incomplete study, for which he used himself as the subject. He tried to memorize nonsensical syllables, testing himself repeatedly at different time intervals and recording the results. Based on these results, he created a graph that is now known as the “forgetting curve.” However, the scientist only studied the rate of forgetting, and he did not focus on the effect on memorization of repetition at intervals.

From the graph below, which shows the forgetting curve, you can see that with each successive reminder of material, the forgetting curve “flattens out.” This means that the information stays in your head for longer and it takes much longer to forget.

Hermann Ebbinghaus formulated the hypothesis that the rate of forgetting depends on many factors, such as the difficulty of the material to be remembered (for example, it would be easier to remember actual words rather than meaningless syllables), how the material is presented, and physiological factors such as stress and sleep.

Spaced Repetition

The term “spaced repetition” itself did not appear until the 1930s.

The idea that spaced repetition can be used to improve the learning process was first suggested in the book The Psychology of Study by Professor C. A. Mace in 1932. In this book he stated:

Perhaps the most important findings concern the proper distribution of learning periods…. Repetitions should be spaced at gradually increasing intervals, roughly at intervals of one day, two days, four days, eight days and so on.

C. A. Mace

Later research in the 1970s and 1980s, conducted by Landauer, Bjork, Schacter, Rich, Stampp and others, showed that the spaced repetition method was effective not only for learning and remembering faces and names, but also for people with memory disorders such as amnesia or Alzheimer’s disease.

The method was popularized by German scientist Sebastian Leitner in 1972, and it is still known today as the “Leitner box”. In this method, pieces of paper with information are sorted into groups according to how well the learner knows each one. Learners try to recall the answer written on the back of the paper. If they succeed, they move the card to the next group. If they fail, they send it back to the first group. For each successive group, students reach back after a longer period of time than for the previous group.

The spaced repetition method has been developed over the years, and studies have shown that dementia patients using the technique were able to recall information even after several weeks or months. The method has proven effective in helping patients with dementia remember the names of objects, daily tasks, faces and names, information about themselves and many other facts and behaviors.

So when did spaced repetition find its way into language learning?

SuperMemo – using repetition of material at set intervals for language learning

Now let’s talk about Piotr Woźniak. In the 1980s, he was a student at the Poznań University of Technology and studied the effect of sleep on memory. From his research, he found that we actually remember only during sleep. That’s when information from the short-term memory lands in the long-term memory.

Piotr Woźniak struggled to remember material from his studies, so he started developing his own software to be able to remember the material better. The result of his work was the aforementioned SuperMemo algorithm. It was an improved idea of repeating material at specific intervals. The second version of Woźniak’s algorithm (the so-called SM-2) is used by a multitude of applications for learning languages, including Duolingo and Anki.

The real breakthrough, however, came with version 6. It was the first practical way in history to schedule repetitions according to the true Ebbinghaus forgetting curve. Woźniak was even covered by the prestigious Wired magazine in 2008 in the article “Want to Remember Everything You’ll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm.”

SuperMemo lived to see its commercial version. In 1992 it was a finalist in the “Software for Europe” competition at the prestigious CeBIT computer exhibition. In 1997 it was announced by PCkurier as the product of the year in Poland.

Quite often SuperMemo’s developers appropriate the whole idea of spaced repetition to themselves, which, as you can see from the above information, is not true.

Time for repetition – how does it work?

So much for the theoretical side. You’re probably wondering how it works in practice.

Put simply, using this method you first see a word or phrase. Then you have to evaluate how much you know it (know, don’t know, rings a bell). Based on your assessment, the algorithm will schedule a moment for you to “meet” the phrase again. The algorithm will set the time between repetitions, so that the word will appear at a time when you will almost forget it.

To understand this effect a little better, let’s zoom in a little more on how memory works. Roughly speaking, we use two processes during learning:

- input: this learning process is about storing information in the memory.

- output: to be able to use the acquired knowledge later, it is necessary to retrieve it from the memory.

The two processes are not completely separate. Every time you learn something, the brain checks whether the material has already been stored in the memory. It then tries to retrieve previously acquired knowledge. If it turns out that you have already acquired the knowledge in question before and it is presented to you a second time, the knowledge will be stored even better in your memory. The effect is that you can more easily retrieve the material when you need it. So the more often something is offered to you, the easier it is to remember it.

With the Taalhammer app, you don’t have to worry about not knowing when to recall certain material – the algorithm will plan it for you.

My adventure with spaced repetition – part two

I returned to learning using spaced repetition in 2007, when I was 30 years old. At that time there was already a version of SuperMemo UX, for Windows, which was visually much more attractive than the first one.

At that time I started Extreme English: Advanced courses and learned over 4,000 words and sentences in 1.5 years. It was not easy because the words and sentences were not connected. Sentences consisted of words I didn’t know, and the individual words I was learning didn’t appear in sentences. By then I had already begun to wonder if the algorithm would have worked better if the sentences I was learning had been connected to each other.

Despite the difficulties, I managed, graduating with C2-level English and passing the Certificate of Proficiency in English (CPE) language exam.

My adventure with spaced repetition – part three

My third, and definitely not my last, approach to practicing with spaced repetitions took place in 2010. I moved to Amsterdam at that time. Naturally, I started learning Dutch in various language courses.

Having learned by experience, I knew that just attending classes would be of little use if I didn’t revise. What I learned in class, I typed into the SuperMemo app and then repeated. This brought sensational results – compared to other students, I was making huge progress, and I knew a lot of words – but I didn’t achieve grammatical fluency. I couldn’t form complex grammatical constructions in conversation.

So I started analyzing my results, wondering what went OK and what was missing. Then I realized that I had again made a fundamental mistake – I was typing sentences that had nothing to do with each other. I was simply rewriting them from a book, or from notes taken in class.

The second mistake was that I didn’t start speaking right away, from the first class. At that time, I was sure that I would start speaking after some time. I thought it was better to wait until I knew a lot of words and only then would I use them in conversation. As a result, I didn’t have the opportunity to activate all the constructions I was learning. I can say that I wasn’t really learning language, but words and structures.

So I became even more interested in the topic of language learning and met linguist Stephen Krashen,who created the “Hypothesis of Language Acquisition“. This focuses on the difference between language acquisition and language learning. It is a process in which a language learner “acquires” new linguistic skills, subconsciously, through exposure to language in real communication situations. This process resembles a child’s natural language acquisition. According to Krashen, language acquisition is more efficient and leads to permanent language acquisition. That’s when I realized the importance of creating a learning system in which students start using the language right away, and in the most natural situations possible.

My adventure with spaced repetition – part four

In 2013 I met Anna, a girl from Italy, and started learning Italian. On top of that, I was planning to go on vacation to Sicily – English is unlikely to be used there. However, instead of repeating the mistakes of the past, I learned from them to master the new language as quickly as possible.

First of all, I started speaking right away, using the vocabulary I was learning. Over time, it began to expand. I also watched movies and started listening to Italian music. Learning a language by listening to songs is an excellent and interesting way to build a vocabulary base, as well as discover grammar.

I wanted to continue using language learning apps, but I started doing something new. Instead of typing words out of context, I pasted a lot of variations of the same grammatical constructions into SuperMemo, using the same words. For example, I created 20 sentences with the word “although,2 or 30 sentences in the conditional mood. I conjugated the same verb a lot by different persons in different tenses. If I learned something in courses, I immediately typed everything into the app.

Regular repetition combined with the additional methods I implemented made the results exceed my expectations. After six months of learning, I went to Sicily. I drank some wine to give myself courage and started talking to Italians. Of course, these were no advanced conversations on serious topics, but I was able to communicate with them and have a nice time. I still remember that wonderful moment when the words and sentences I was learning seemed to flow on their own and create a conversation. I proved to myself that it is possible to achieve fluency (limited, of course) in a foreign language in just six months.

After two years of studying, I went to Milan for a week-long Italian course. The first time I spoke to the teacher over lunch, I realized that I was automatically using the plethora of words I had learned with SuperMemo. And best of all, I was doing it in a fluent way. After completing the course, I decided that from then on I would only speak Italian with my girlfriend, and in 2015, after two years of study, I passed the B2 exam.

Can you learn even more efficiently?

My success in learning Italian got me thinking about how the app’s algorithm could be improved by adding other elements to the interval repetitions.

First, instead of giving whole, long and complicated grammar rules, I decided to create short grammar clues that can help you understand grammar.

In SuperMemo, you have to grade yourself. I, however, wanted to make learning convenient – if possible hands-free. So I created a language radio, whose list is managed by an algorithm. This way you can learn at the gym, in the car, in the grocery line, wherever your hands are busy.

I also realized that a great part of learning is the listening materials, which consist only of vocabulary you already know. So they are 100% understandable.

To improve pronunciation and sound recognition, I also added an IPA phonetic transcription that I worked on during my studies.

Atom – new algorithm, even better language learning

Based on my learning experience, I created a recipe for effective language mastery for everyone. However, I needed a tool that could realize it. That’s why I started working on my own algorithm, which would take into account all the aforementioned aspects of learning.

I started my work by analyzing the SM-15 algorithm. I also started generating sentence variations using artificial intelligence. My goal was to create a list of the most frequently used words in the language, for example, “go,” “often,” speak,” “work,” etc., as well as the highest possible variance of sentences containing these words. I also decided that the sentences should use different grammatical structures for the level – for example, in the A1 level there would be sentences in the present tense, questions, negations, future tense, plurals, etc.

I wanted the product I would offer to others to be the best possible. So it was important to take some time for me to be my own guinea pig and test on myself how quickly I was able to memorize the given structures. Based on trial and error, I improved the algorithm.

In the meantime, I also tested the effects of sports training, meditation, and sleep on memory. It turned out that all of these, combined with the right techniques, produce spectacular results. For example, studies unanimously indicate that physical activity during the learning process has a positive effect on memory capacity and information retention. Performing exercise, such as weight lifting, cycling, walking, running, aerobics, or any other type of physical activity, contributes to significant changes in brain biology. These changes make the brain more receptive to learning by increasing the flow of oxygen and the amount of neurotransmitters.

In 2017, I was joined by Łukasz, who also has extensive experience with language learning, the spaced repetition method and software engineering. So we joined forces and further tested and improved the algorithm. Then the development picked up speed and form. In 2019, we have already noticed truly amazing results. It was also the time when our algorithm got its name. Atom Algorithm was the basis for the creation of Taalhammer.

Taalhammer today is your personal language coach created from our passion for language learning, backed by science, powered by AI technology and verified by experience.

Our app uses our personal experience, as well as years of research on memory, learning techniques and psychology. That’s what makes it so highly effective. Join us in our mission!