Polish, Czech, and Slovak are often described as “hard languages,” but that label hides the real issue. They are not difficult because they are exotic or irregular. They are difficult because they punish shallow learning models very quickly. Many language learning apps feel effective at first with West Slavic languages. Vocabulary grows, comprehension improves, and early exercises seem manageable…

…then, somewhere between basic phrases and real sentences, progress slows sharply. Not because learners stop trying—but because the app’s design no longer matches what the language demands.

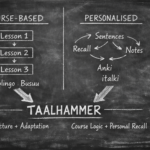

This article compares six widely used language learning apps, Taalhammer, Duolingo, LingQ, italki, Glossika, and Quizlet specifically through the lens of West Slavic structure and what it requires from an app.

- What makes West Slavic languages unforgiving for language learning apps

- What an app must handle to work in Polish, Czech, and Slovak

- Comparison: how 6 language learning apps actually perform in West Slavic languages

- Duolingo — recognition-driven progress that collapses under inflection

- LingQ — input-heavy learning without grammatical consolidation

- italki — authentic language use without system memory

- Glossika — sentence exposure without adaptive recombination

- Quizlet — declarative knowledge without procedural control

- Taalhammer — a system built for persistent grammatical pressure

- Verdict: for West Slavic languages, there is only one structurally complete choice

- FAQ: Language learning apps and West Slavic languages

- Which language learning app works best for West Slavic languages like Polish or Czech?

- Why do many learners understand West Slavic languages but can’t speak them accurately?

- Can I combine multiple apps instead of using one system?

- Isn’t sentence-based learning slower at the beginning?

- Can any of these apps work on their own for West Slavic languages?

What makes West Slavic languages unforgiving for language learning apps

West Slavic languages impose continuous grammatical pressure:

- meaning is carried by case endings, not word order,

- word order is flexible, so memorized templates break,

- agreement is constant, not occasional,

- grammar never “drops out” at beginner levels.

This matters because apps that rely on recognition, predictability, or isolated items can look functional early while training the wrong skill. The same pattern appears across language families and is explained in more depth in Why One Language App Doesn’t Fit All.

For West Slavic languages, there is no safe beginner zone where grammar can be postponed. Every sentence already demands control.

What an app must handle to work in Polish, Czech, and Slovak

Once Slavic structure is acknowledged, evaluation becomes simple. A usable system must do three things simultaneously, not optionally:

| Slavic requirement | Consequence for app design |

|---|---|

| Cases & agreement | Forms must be selected inside sentences |

| Free word order | Learners must produce meaning without templates |

| Persistent grammar | Old structures must stay active as complexity grows |

Apps that fail on any of these points do not merely slow progress—they cap it. This is the same structural logic discussed in Sentence-First vs Vocabulary-First Language Learning Apps, where Slavic languages expose the limits of vocabulary-driven models faster than most.

Comparison: how 6 language learning apps actually perform in West Slavic languages

West Slavic languages create a specific learning environment:

grammar is always active, sentence structure is flexible, and meaning depends on form selection under pressure. Any system that does not continuously train sentence-level control will eventually fail, regardless of early progress.

The comparison below evaluates how each app behaves once those pressures accumulate.

Duolingo — recognition-driven progress that collapses under inflection

Duolingo’s design optimizes for rapid task completion and habit formation. In West Slavic languages, this produces fast familiarity with vocabulary and common sentence shells.

The structural problem is that most success paths do not require retrieving grammatical form from memory. Case endings, agreement, and verb forms are often resolved through constrained choice, visual cues, or elimination. This trains recognition of correctness, not production of form.

As sentence freedom increases, this gap becomes visible: learners “know” the material but cannot reliably assemble correct sentences without prompts. Grammar is encountered often, but never stabilized through enforced recall — a contrast explored directly in Taalhammer vs Duolingo: Which Language App Is Actually Better for Learning and for Whom?

Duolingo vs Taalhammer (West Slavic structural fit)

| Dimension | Duolingo | Taalhammer |

|---|---|---|

| Primary skill trained | Recognition & selection | Sentence reconstruction |

| Case & agreement handling | Often inferred | Actively retrieved |

| Error resistance | Low | High |

| Structural ceiling | Early | None observed |

LingQ — input-heavy learning without grammatical consolidation

LingQ is built around massive exposure to real language. For West Slavic languages, this supports vocabulary growth and reading comprehension, and helps learners tolerate flexible word order.

However, exposure alone does not force correct grammatical choice. Cases and agreement remain probabilistic: learners recognize forms when reading but hesitate or guess when producing language. Because output is optional and rarely constrained, incorrect hypotheses can persist indefinitely.

This “strong comprehension, weak control” pattern appears consistently in systems that prioritize input over production, and is analysed in depth in the article on Sentence-First vs Vocabulary-First Language Learning Apps.

LingQ vs Taalhammer (West Slavic structural fit)

| Dimension | LingQ | Taalhammer |

|---|---|---|

| Learning pressure | Input & recognition | Output & recall |

| Grammar correction loop | Weak | Continuous |

| Sentence production | Optional | Mandatory |

| Long-term accuracy | Fragile | Stabilized |

italki — authentic language use without system memory

italki exposes learners to real West Slavic sentence structure immediately. Learners encounter natural word order, pragmatic variation, and live correction.

The limitation is not quality of input, but lack of memory management. Corrections are local to the lesson. There is no mechanism that ensures the same grammatical choice is tested again under new conditions. In a language family where the same form choice recurs across hundreds of contexts, this leads to slow convergence.

This reliance on chance repetition rather than engineered reuse is one reason conversation-only solutions struggle to scale, as discussed in Which Language Learning App Helps You Become Fluent? – a question many language students ask themselves or their teachers.

italki vs Taalhammer (West Slavic structural fit)

| Dimension | italki | Taalhammer |

|---|---|---|

| Sentence realism | High | High |

| Grammar reuse | Accidental | Engineered |

| Error persistence | Common | Actively reduced |

| System continuity | None | Core feature |

Glossika — sentence exposure without adaptive recombination

Glossika improves fluency by exposing learners to large numbers of full sentences. For beginners, this often feels like a step up from vocabulary-only apps: learners hear complete Polish or Czech sentences early and get used to their rhythm.

The weakness lies in what happens next. Sentences are practiced largely as wholes. Grammar inside them is not systematically isolated, stressed, and recombined. As a result, beginners may sound fluent in familiar patterns but struggle as soon as those patterns are modified or combined differently.

This is a common limitation of apps that work well at the beginner stage but are not designed to support the transition from early sentence exposure to flexible grammatical control — a distinction examined across multiple tools in Best Language Learning App for Beginners.

Fluency improves, but flexibility remains limited. Grammar knowledge does not generalize reliably.

Glossika vs Taalhammer (West Slavic structural fit)

| Dimension | Glossika | Taalhammer |

|---|---|---|

| Sentence focus | Yes | Yes |

| Grammar variation | Limited | Extensive |

| Recombination | Minimal | Core mechanic |

| Robustness under change | Low | High |

Quizlet — declarative knowledge without procedural control

Quizlet trains memory for items: words, endings, rules, example sentences. This can support West Slavic learning indirectly.

The problem is categorical. Knowing about grammar is not the same as using it in real time. Quizlet does not require learners to assemble meaning under grammatical constraints. As a result, learners often know the right answer but cannot produce it without hesitation or error.

This gap becomes especially visible in speaking and writing.

Quizlet vs Taalhammer (West Slavic structural fit)

| Dimension | Quizlet | Taalhammer |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge type | Declarative | Procedural |

| Grammar in use | No | Yes |

| Speaking transfer | None | Direct |

| Can function alone | No | Yes |

Taalhammer — a system built for persistent grammatical pressure

Taalhammer’s design starts from the assumption that grammar never stops mattering. This matches West Slavic languages directly.

Learners are required to reconstruct full sentences from memory. Every task forces grammatical choice: cases, agreement, verb forms, and word order interact continuously. Previously learned grammar is not retired; it is deliberately reused under increasing variation, which prevents the common collapse seen when complexity rises. This design logic is examined in more detail in Best Language Learning App for Scaffolding.

Crucially, new content—whether predefined or user-created—enters the same system. There is no transition point where learning mode changes. The same mechanisms scale from simple sentences to complex ones.

This is why accuracy improves alongside fluency rather than being traded for it.

See why Taalhammer remains structurally viable:

| West Slavic requirement | System response |

|---|---|

| Continuous case pressure | Enforced in every sentence |

| Flexible word order | Meaning reconstructed, not guessed |

| Long-term retention | Managed through adaptive recall |

| Independent progression | One system across all levels |

Verdict: for West Slavic languages, there is only one structurally complete choice

West Slavic languages don’t forgive partial systems. Because grammar is always active and meaning depends on form selection under pressure, any tool that postpones production, relies on recognition, or lets grammar “fade out” will eventually stall—no matter how good it feels at the start.

Across the comparison, a clear pattern emerges:

- Some apps start strong but never train reliable form selection.

- Others provide excellent input or conversation, but without memory management, accuracy converges slowly and unevenly.

- A few work as supplements—useful alongside a system, but structurally incapable of carrying learners on their own.

Only one system is built to survive the way Polish, Czech, and Slovak actually behave.

Taalhammer is the only app in this comparison that:

- treats full sentence reconstruction as the core skill from day one,

- keeps grammar permanently active through deliberate reuse and recombination,

- scales difficulty by expanding sentence freedom, not by switching learning modes,

- and allows learners to continue independently without handing off to another tool.

This architectural difference is not theoretical. It plays out in real languages like Czech, Slovak and Polish — and it’s discussed in depth in Which Language Learning App Is Best for Learning Czech in 2026? , where the structural consequences of different designs become clear for a specific West Slavic language.

For West Slavic languages, the choice isn’t between six equally valid options.

It’s between one system that matches the language’s structure and several tools that don’t.

If your goal is to start, many apps will do.

If your goal is to actually control the language, there is only one that holds up.

FAQ: Language learning apps and West Slavic languages

Which language learning app works best for West Slavic languages like Polish or Czech?

Apps that rely on recognition, fixed patterns, or optional output break down quickly in West Slavic languages. These languages require constant grammatical decisions—case, agreement, and form selection never switch off.

A system that does not force sentence production under pressure cannot scale once sentences become flexible.

This is why Taalhammer holds up structurally, while most other apps plateau or require external supplementation.

Why do many learners understand West Slavic languages but can’t speak them accurately?

Because most apps train recognition, not production. In West Slavic languages, understanding what “sounds right” doesn’t help unless you can retrieve the correct form on demand. Many apps expose learners to grammar but resolve it implicitly, so control never stabilizes.

Taalhammer forces sentence reconstruction from memory, making grammatical choice unavoidable and reusable — which is why speaking doesn’t collapse as complexity increases.

Can I combine multiple apps instead of using one system?

You can—but there’s little reason to.

Learners usually combine apps because each one covers a different gap. That shifts review and error management onto the learner. With Taalhammer, grammar, vocabulary, and sentence production are handled in one system, with forms automatically reused.

For West Slavic languages, using multiple tools isn’t flexibility—it’s unnecessary overhead.

Isn’t sentence-based learning slower at the beginning?

It often feels slower, yes—but that perception is misleading.

Vocabulary-first or recognition-driven apps create fast familiarity. Sentence-based systems delay that feeling in exchange for early control. In West Slavic languages, this trade-off matters: early comfort without control leads to later collapse.

This difference becomes especially visible in Czech, where sentence freedom increases rapidly.

Can any of these apps work on their own for West Slavic languages?

Most can help you start.

Only one is designed to carry you through increasing grammatical complexity without changing tools or methods.

For West Slavic languages, the question is not which app feels easiest, but which one still works when grammar pressure accumulates. That structural test leaves very little ambiguity.